The Iron Age,

written in iron

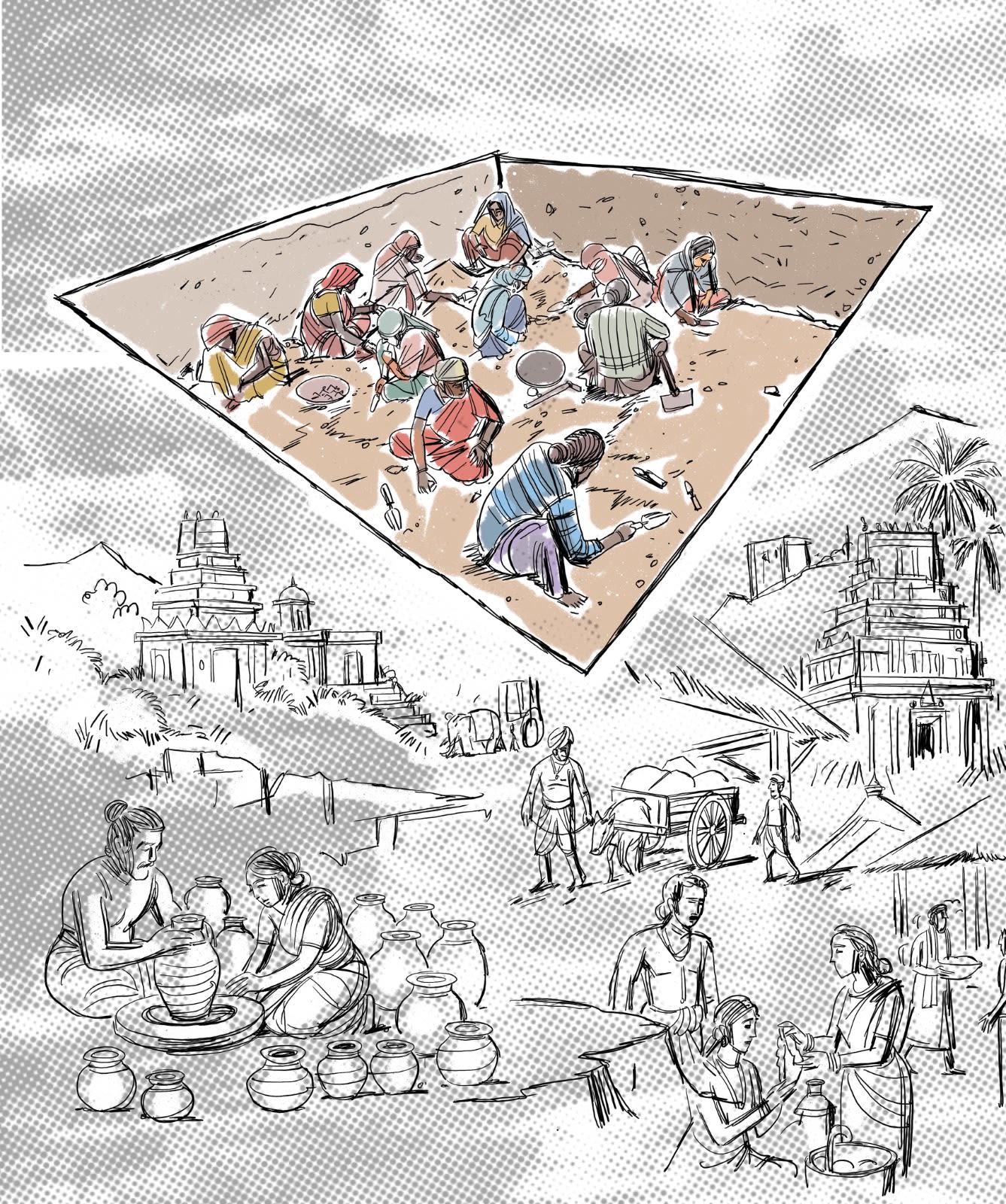

Archaeological excavations in Tamil Nadu have revealed significant evidence of ancient civilisations, including the Sangam Era and Iron Age. Key sites like Keeladi, Sivagalai, and Adichanallur have been instrumental in pushing back the timelines of the Sangam Era and revealing evidence of advanced iron technology.

The excitement of discovery

As the car turns left off a bridge across the Thamirabarani River onto a desolate road, history teacher A Manickam’s eyes brighten. This is the same path where he spent much of his free time, often earning the ire of his wife. The car nears a shed covered with blue asbestos sheets, and Manickam can't hide his excitement. “This is the Sivagalai Archaeological Site,” he says.

It was Manickam’s relentless pursuit and repeated petitions to the government that led to the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology (TNSDA) launching excavations in this nondescript village in Thoothukudi district. Manickam had always been confident that this barren land, which he passed daily while dropping his children at school, could yield surprises. He frequently found potsherds and other antiquities scattered along the path. Little did he know that his efforts would lead to the discovery of a site with the potential to rewrite history.

|

A timeline |

||

|---|---|---|

|

3345 BC |

2200 BC Gachibowli (Telangana) |

2172 BC Mayiladumparai (Tamil Nadu) |

|

2140 BC |

1200 BC |

Sivagalai predates all known sites by over a millennium |

|

Scientific dating techniques |

|---|

|

AMS (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) |

|

OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence) |

|

Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) |

||

|---|---|---|

|

AMS is a high-precision technique that measures carbon-14 isotopes to date ancient organic materials, even in very small samples. |

||

|

Keeladi findings: Six carbon samples from Keeladi, tested at Beta Lab (Florida), were dated between 580 BC and 300 BC. |

||

|

Depth-based timeline: Samples from 353 cm depth date to the late 6th century BC; from 200 cm, to the early 3rd century BC. |

|

Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) |

||

|---|---|---|

|

OSL dating measures trapped energy in |

||

|

OSL helps date sediment layers and confirms timelines of ancient human activity and |

||

|

Samples are tested at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow, and Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad using the OSL method. |

|

DNA & Isotope findings |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Analyses at burial sites like Adichanallur and Sivagalai trace the genetic ancestry and migration patterns of the Iron Age in Tamil populations. |

||

|

TNSDA is investigating technological changes in Iron Age tools, comparing early and later iron artefacts for shifts in |

||

|

Studies aim to identify whether magnetite or laterite ores were used and how furnace types varied regionally, e.g., Mettur vs Pudukkottai. |

||

|

Other initiatives by TNSDA |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Graffiti & Indus link: |

||

|

Tamili script evidence: |

||

|

Extensive excavations: |

Rewriting the

history of iron

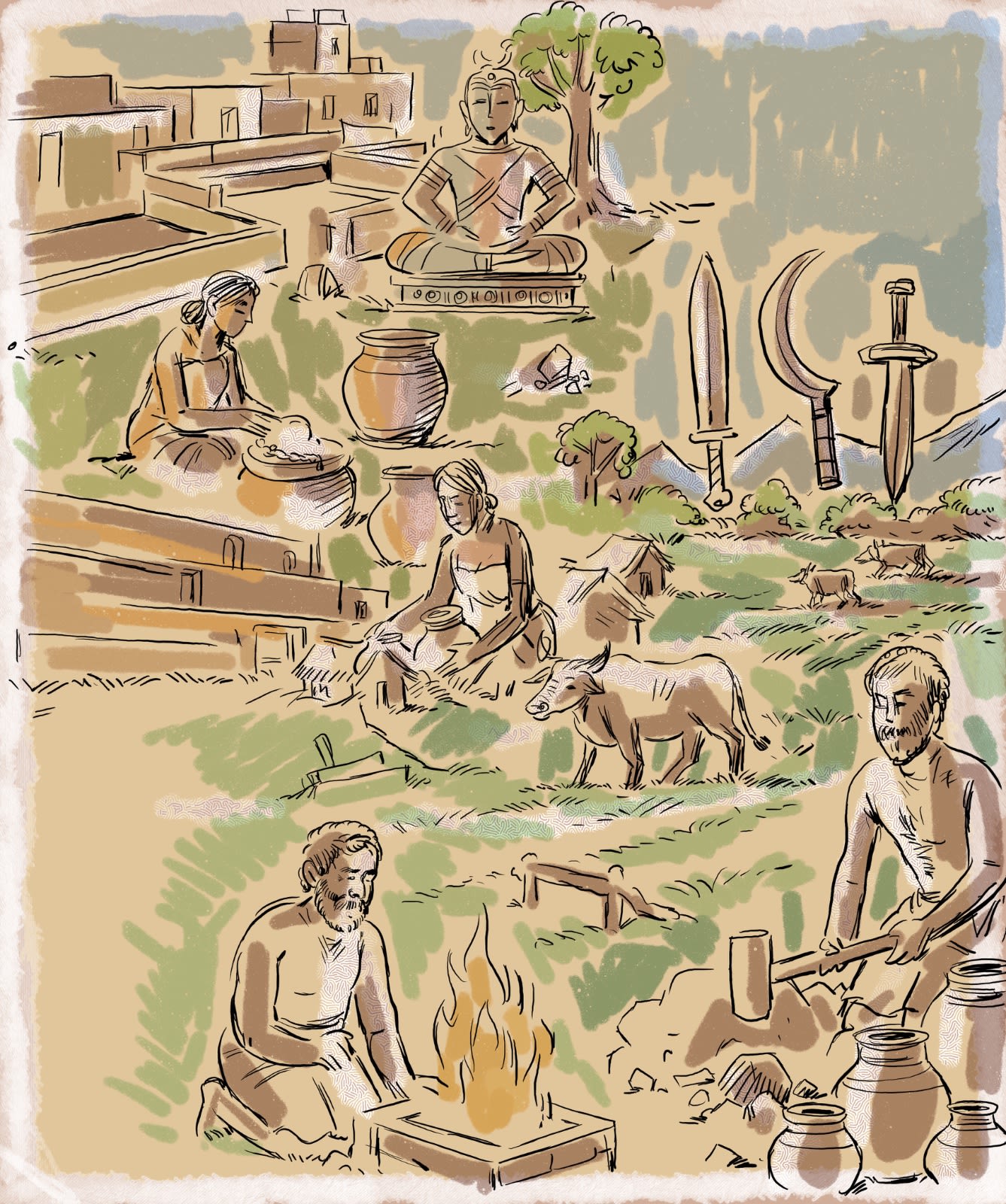

The trenches, filled with urns surrounded by offering pots, reveal the rich past of the ancient Tamils. Iron implements found at the site, located on the left bank of the Thamirabarani River, have been dated to 3345 BC, the earliest known date for smelted iron, not just in India but anywhere in the world.

Three laboratories, using two techniques — Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) and Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) — dated the iron implements from Sivagalai to between 2427 BC and 3345 BC. AMS dates from other sites in the state, like Kilnamandi, Mayiladumparai, Thelunganur, and Mangadu, also helped consolidate these findings. The results, published in the report Antiquity of Iron by TNSDA in January, push the introduction of smelted iron in India back by over a millennium. This discovery positions the region as a pioneering hub of early metallurgy, surpassing global timelines.

Challenging established perceptions

The new dates have prompted archaeologists to conclude that iron was introduced to South India during the middle of the 3rd millennium BC (2500–3000 BC). Interestingly, two dates (3259 BC and 3345 BC) from Sivagalai even fall in the first quarter of the 4th millennium BC. This challenges the widely held belief that the Iron Age began around 1200 BC in Anatolia by the Hittites, and if scientifically confirmed, could make these findings the oldest known instances of iron smelting.

From passion to recognition

Manickam’s excitement led him to send photos of the mound to Finance Secretary T Udhayachandran, who was then the Archaeology Commissioner. As a result, Sivagalai was added to the list of sites to be excavated. The TNSDA conducted three phases of excavation from 2020 to 2023, leading to these groundbreaking discoveries.

Sivagalai has proven to be a significant site in India’s archaeological heritage. In 2021, paddy husks found in a burial urn and a Tamil-Brahmi inscribed potsherd from a nearby habitation site were dated to 1155 BC (3,200 years old) and 685 BC (2,700 years old), respectively. Another critical takeaway from these findings is the reinforcement of the idea that iron technology in India was homegrown, and never imported from the West — a theory long championed by experts like Prof Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti.

A political dimension

The findings were endorsed by at least ten experts from across India and were released by Chief Minister M K Stalin in January. Stalin had in 2021 declared that his government would scientifically prove that India’s history should be rewritten from the Tamil landscape, emphasising its role in early urban culture, literacy, and trade networks. Since then, the DMK government has generously funded the TNSDA, allocating a record Rs 5 crore annually for excavations. Excavations have since extended across almost every part of Tamil Nadu, in line with

Stalin’s mission to uncover the ancient Tamils’ lives and contributions.

Key archaeological sites in TN

Thelunganur (Salem district)

Iron artefacts, including a sword dated to 1435–1233 BC, point to early metallurgy.

Evidence suggests independent iron technology as far back as 3345 BC.

Mangadu (Salem district)

Produced an iron sword dated to 1510 BC, highlighting ancient steel-making skills.

Reveals a sophisticated metallurgical culture predating conventional Iron Age dates.

Vembakottai (Virudhunagar district)

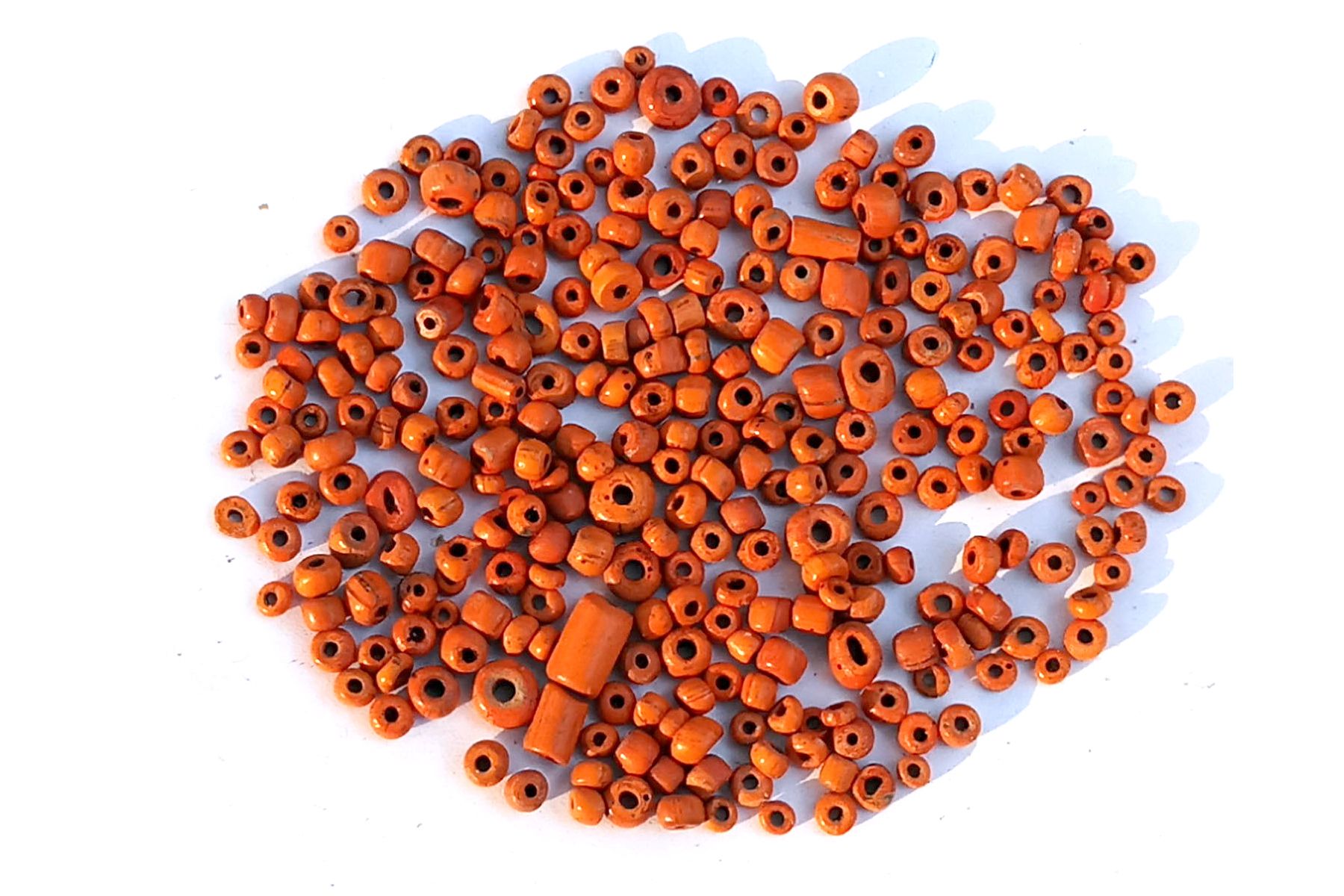

Excavations unearthed shell bangle and bead workshops from the 1st century BC–CE.

Over 12,000 artefacts highlight Early Historic industrial trade under the Pandyas.

Chennanoor (Krishnagiri district)

Neolithic site with microliths, handmade pottery, and rare burnished ware.

Findings bridge the Microlithic to Early Historic period in Tamil Nadu.

Kodumanal (Erode district)

A key trade hub near the Noyyal River with Megalithic and Early Historic layers.

Pottery types and industrial remnants link it to the Chera port of Muziris.

Adichanallur (Thoothukudi district)

Early Iron Age burial site with 169 urns unearthed along the Thamirabarani River.

Excavated since 2004, it's now protected with a museum showcasing skeletal remains and artefacts.

Mayiladumparai (Krishnagiri district)

Charcoal-dated to 2172 BC, once India’s earliest known Iron Age site.

Artefacts span from Microlithic to Early Historic periods with strong local metallurgy.

Phase-wise details from Keeladi

Phase I & II

(ASI)

2014-2015

Artefacts found: 5,765

Iron objects, Carnelian beads, and five different kinds of ring wells. Terracotta objects like human and animal figurines, pendants, ivory objects, metal, glass, and stone objects. Iron objects, and some silver punch-marked coins.

Phase III

(ASI)

2015-2016

ASI declared no significant findings and decided to stop excavating. P S Sreeraman, who replaced K Amarnath Ramakrishna as the Superintending Archaeologist, declared the same in 2017. Madras High Court then asked the TNSDA to take over the excavations.

Phase-IV (TNSDA)

2017-2018

Artefacts found: 5,820

Brick structures, gold ornaments, iron implements, terracotta toys,

figurines, beads of glass and black and red ware, Tamili (Tamil-Brahmi)

inscribed potsherds, bones of a bull with hump, and brick walls. Traces of advanced urban planning.

Phase-V & VI (TNSDA)

2018-2020

Artefacts found: 1,800

Iron implements, monolithic tools, terracotta pipes, a closed bridge channel enclosed on four sides with bricks of various sizes, orange Carnelian bead engraved with the image of a wild boar. Human skeletons, furnaces and utensils.

Phase-VII (TNSDA)

2020-2021

Artefacts found: 2,000

Offering vessels of various shapes and sizes were found inside the urns, and this demonstrates the

dignity the inhabitants accorded to the dead.

Phase-VIII (TNSDA)

2021-2022

Artefacts found: 2, 200

Rectangular cube-shaped dice made of ivory and terracotta, and some Carnelian

beads, a terracotta human head figurine, and some ear ornaments made of ivory.

Phase-IX (TNSDA)

2022-2023

Artefacts found: 804

A weighing unit made of crystal quartz that was transparent in nature, a handmade snake figurine, some glass beads, glass bangle fragments, and gold wire.

Phase-X (TNSDA)

2023-2024

Artefacts found: 756

Evidence shows domestic life among ancient inhabitants, including well-planned living quarters, terracotta pipelines, several storage jars and Tamil-Brahmi sherds.

Amarnath Ramakrishna: The man behind Keeladi’s discovery

KAmarnath Ramakrishna, then Superintending Archaeologist with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and a native of Palani, led the team that uncovered Keeladi — a major urban settlement on the banks of the Vaigai (Vaiyai in Sangam literature), 12 km from Madurai.

The excavation revealed artefacts suggesting an industrialised civilisation dating back 2,600 years and pushing the literature-rich Sangam Era behind by at least three centuries than it was thought to be. Ramakrishna became a familiar face in Tamil

media, offering insights into Keeladi’s historical significance.

However, his 2017 transfer to Assam sparked protests from Tamil Nadu political parties, who claimed he was being “punished for speaking the truth.”

“This is purely a Sangam Age site,” he had told DH in 2023. “We found evidence of a continuous urban settlement. The findings are only the beginning — Keeladi may hold more surprises as excavations continue.”

Controversy in archaeology

The transfer of Ramakrishna sparked a debate over the

politicisation of archaeology. After his transfer in 2017, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) attempted to wind up excavations at Keeladi, but the Madras High Court intervened, directing the TNSDA to take over. The findings from Keeladi, particularly the discovery of silver punch-marked coins, have challenged the belief that South India lacked an ancient urban civilisation. These coins, bearing symbols like the sun, moon, and bull, suggest trade links between Keeladi’s inhabitants and northern India.

Delays and tensions

Ramakrishna submitted a comprehensive 982-page report on Keeladi’s findings to the ASI in January 2023. However, after two and a half years, the ASI requested revisions, citing expert comments. This delay was widely seen as a political move by the BJP to slow the recognition of Keeladi’s antiquity. Despite this, Ramakrishna stood firm, dating the site to between the 8th century BC and 3rd century CE. In what many saw as a punitive move, he was transferred from the ASI headquarters in New Delhi to the National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities in Greater Noida.

|

What was found at Sivagalai |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Burial urns with |

Iron implements (chisel, tools) |

Tamil-Brahmi inscribed potsherd (685 BC) |

The discovery of Sivagalai

Sivagalai's discovery is also tied to the exploration of other Iron Age sites in Tamil Nadu. Adichanallur, 26 km from the ancient Pandya capital of Korkai, has long been considered a promising site. It was excavated by ASI in 2004, revealing 169 clay burial urns across 114 acres. In 1939, ASI Director-General K N Dikshit had already speculated that a "thorough investigation" in the region would uncover a site contemporary with or even earlier than the Indus Civilisation.

|

Sivagalai: Redefining the timeline of Iron Age |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Sivagalai was chosen for excavation in 2019 after teacher A Manickam found |

Three excavation phases by TNSDA unearthed 681 artefacts, including iron swords, chisels, and knives. |

Earliest dates: |

|

Samples dated by three labs (Florida, Lucknow, Ahmedabad) gave results between 2427–3345 BC. |

An iron implement dated to 3345 BC challenges the belief that India’s Iron Age began around 1200 BC. |

Suggests South India entered the Iron Age over 2,000 years before North India. |

A teacher’s vision

Manickam's instincts about the potential of the barren land near Sivagalai were spot on. “I was sure that the barren land I wandered every day could hold secrets of ancient Tamils,” he said. His persistence in petitioning government officials and the subsequent support of Archaeology Commissioner Udhayachandran set the wheels of discovery in motion. What started as a teacher’s curiosity has now blossomed into one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in recent history.

The beginning of

excavation at Sivagalai

In 2019, a team from the TNSDA inspected a huge archaeological mound in Sivagalai and recommended its addition to the list of excavation sites. Although the mound had been disturbed, with much of the sand removed, the team concluded that the area could have been a burial site of the ancient Tamils.

Challenges & doubts

during excavation

When M Prabhakaran, the excavation director, began the excavation, he was initially unsure of its success. For the first three weeks, no discoveries were made. "I began to question myself whether we had chosen the right site. We kept digging trenches, but couldn’t find anything," Prabhakaran said. But after about a month, the situation changed dramatically.

The breakthrough came when a burial urn was unearthed, marking a turning point for the excavation. “There was no looking back. Every moment since then was exhilarating,” Prabhakaran recalled. During the first phase, all 11 samples that were recovered, including a chisel, were sent for analysis which helped date the site to 3345 BC.

The discovery of a habitation site

In addition to the burial site, archaeologists also discovered a habitation site 3 km away at Valapanpillaithiradu, where a Tamil-Brahmi sherd inscribed with "Atan" was dated to 685 BC. "The stratigraphical position of black-and-red ware in the habitation mound was identical to what we found in the burial sites," said Prof K Rajan, co-author of Antiquity of Iron. The samples from the habitation site were found to be contemporary with the burial site, dating back to 2522 BC.

Key finds & dates

Among the significant finds was paddy, dated to 1155 BC, unearthed from an offering pot in Trench A2. Meanwhile, carbon from two urns and associated iron objects, including three chisels, were dated to 3345 BC in Trench B3. The 10-metre gap between Trenches A2 and B3 emphasises the extensive timeline of the site.

Despite the initial success, later phases of excavation were more challenging. Due to the disturbed nature of the archaeological mound, most of the urns recovered in the second and third phases were fragile, and fewer iron objects were found compared to the first phase. “We couldn’t get samples intact in the second and third phases due to the disturbed nature of the site,” Prabhakaran explained.

The findings from Sivagalai come after controversial excavations at Keeladi, which also faced scepticism from some archaeologists. This time, however, the Stalin administration was careful in its approach. The government invited renowned Iron Age experts, such as Prof Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti, Professor Emeritus of South Asian Archaeology, Cambridge University, UK, and Rakesh Tewari, former Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), to endorse the findings.

Stalin’s government also took significant steps to digitise over 15,000 graffiti-inscribed potsherds from 142 sites in Tamil Nadu, with studies revealing that 90% of the signs matched those found in the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), although only 60% aligned with IVC seals. Stalin even announced a USD 1 million reward for deciphering the Indus script, which many believe may be linked to Tamil writing.

Caution, despite the

compelling evidence

Despite the compelling evidence, archaeologists remain cautious about drawing premature conclusions. While two dates — 3259 BC and 3359 BC — fall in the first quarter of the fourth millennium BC, the mean date of around 2500 BC is considered the earliest date for the Iron Age in the region.

“Sivagalai is currently the earliest Iron Age site,” said Rajan. “Further excavations in South India’s iron ore-rich zones could push this date even earlier.”

The global significance

of the findings

Experts like Tewari, former Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and Ravi Korisettar, Adjunct Professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, have emphasised that the scientific dating methods used by TNSDA are unquestionable. Tewari, who had predicted an earlier Iron Age date for South Asia back in 2004, noted that the new evidence supports placing the antiquity of iron in Tamil Nadu around 2500 BC, making it the earliest known evidence of smelted iron globally.

The findings from Sivagalai confirm Prof Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti's long-standing hypothesis that iron technology in India was homegrown. "We now have solid evidence to show that iron technology used in India was our own," Tewari said, underscoring the importance of these new dates in challenging colonial-era assumptions about the origins of iron technology.

The challenges to linear

technological development

The new dates from Sivagalai challenge the notion of a linear technological development. According to Korisettar, the early use of iron in Tamil Nadu should be understood within its unique cultural and environmental context, rather than fitting it into a uniform progression across India. “Different regions of the world, and within India, followed distinct developmental paths,” Korisettar explained, “rendering the linear Stone Age–Copper Age–Iron Age model inapplicable universally.”

The role of resource availability

in technological development

Experts believe that bronze technology does not necessarily predate or follow iron technology due to resource availability. “It depended on human communities’ ability to identify resources and develop technology to extract iron from ore. One technology did not necessarily lead to another,” Korisettar clarified.

Cultural & historical

variations across India

“I accept these dates because different parts of India have their own unique cultures and histories,” Korisettar continued. “For instance, the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) was distinct from other regions, and southern India’s Neolithic culture differed from the Chalcolithic culture in the northern Deccan, even though they existed around the same time.”

He also emphasised, “Soon, we will understand that different regions in India have their own separate histories. Science warns us not to jump to conclusions too quickly, and there should be no scope for jingoism.”

Southern TN's unique transition

In southern Tamil Nadu, sites like Sivagalai and Adichanallur show a direct transition from the Microlithic to the Iron Age, bypassing the Neolithic or Chalcolithic phases. This contrasts with northern Tamil Nadu, where a clear Microlithic–Neolithic–Iron Age sequence is evident.

R Balakrishnan, an expert on Tamil culture, noted, “The availability of natural resources determined the nature of the Metal Age. However, the Tamil Sangam Corpus is the only literature that equally celebrates both copper and iron use by ancient Tamils. No other literature speaks as highly of both.” Sangam Literature is a multilayered corpus and contains a good share of carried-forward memories of the past embedded in the classical texts, he added.

Rakesh Tewari, fascinated by the leap of the Iron Age into the 3rd millennium BC, endorsed the meticulous research but emphasised the need for more scientific studies. "Archaeological research is continuous, and dates may be pushed back further, especially in regions rich in iron ore,” he added.

Prof K Rajan echoed Tewari's thoughts, explaining that TNSDA will conduct metallurgical analyses of iron slags, crucibles, and ores to understand the technological processes behind South India’s early iron and steel production. “We have dates for finished iron products, but we don’t know where they were manufactured or what technology was used. We have partnered with IIT-Gandhinagar for metallurgical analysis to explore these technological aspects,” Rajan said.

This research could confirm that there were multiple centres of innovation in iron technology, similar to the spread of agricultural practices like paddy cultivation.

Exploring the spread of

iron technology

Tewari offered a new perspective: "It’s possible that in other iron-ore-rich regions, dates might be pushed back further. Where iron technology originated, how it spread, and where it went is still too early to determine. We should wait for more evidence."

Rajan agreed, adding that further excavations and documentation of graffiti marks in neighbouring states like Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Odisha could help clarify the movement of scripts and languages across South India. “These states have more iron ore-bearing zones than Tamil Nadu. If they follow Tamil Nadu’s model of excavation, we can uncover more sites,” he said.

Korisettar praised Tamil Nadu’s archaeological model, saying, “Other states should follow suit. Transparency will help establish credibility. There’s no need to politicise archaeology, as has happened in North India.”

Rajan highlighted that the early adoption of iron in South India was likely due to the region’s abundant iron ore deposits and the scarcity of commercially exploitable copper. “This resource availability likely drove the development of advanced iron and steel technologies, with evidence of steel production in Thelunganur and Mangadu by 1300 BC,” he explained.

Comparing iron resources

in Tamil Nadu & Karnataka

However, Korisettar noted that Tamil Nadu is relatively less rich in iron resources compared to Karnataka, where iron ore deposits were not exploited during the Neolithic period. "In Karnataka, iron objects appear around the early 1st millennium BC, marking the end of the Stone Age without a preceding Chalcolithic phase,” he said.

“In contrast, Tamil Nadu shows evidence of early iron and steel production, particularly at sites like Sivagalai and Kodumanal, earlier than contemporary sites in the Nilgiris or south of the Krishna-Tungabhadra rivers," Korisettar added.

Link between South India

& North India

The findings suggest that by 2500 BC, the entire Indian subcontinent may have been culturally integrated. This challenges the Dravidian hypothesis, which posits that the inhabitants of the IVC migrated to South India.

“The Dravidian hypothesis needs to be re-evaluated,” said Rajan. “Material evidence supports cultural and technological connections between South India and other parts of the subcontinent. Artefacts like Carnelian and agate beads, black-and-red ware, and graffiti marks from Tamil Nadu closely mirror those from the IVC, indicating cultural contact by the 3rd millennium BC.”

Balakrishnan, however, disagreed with the need for a reevaluation of the Dravidian hypothesis. “I believe the AMS and OSL dates reinforce my long-held view that the point at which IVC disappears and Sangam literature begins is the same,” he said.

He considered Sangam Literature a bridge between the IVC and Tamil civilisation, and pointed to metallurgical continuity and similarities between IVC signs and Tamil Nadu’s graffiti as proof of connection.

Early cultural contacts between

North & South India

Tewari also highlighted early cultural interactions between North and South India, noting the presence of Northern Black Polished Ware in Tamil Nadu, initially dated to 400–500 BC. He proposed that this pottery, associated with deluxe production in Magadh (Bihar), indicated earlier interactions — a view now widely accepted. These interactions likely facilitated the exchange of cultural artefacts, ideas, and possibly even iron technology.

As Neolithic cultural subdivisions began merging, agro-pastoral communities spread throughout India, bringing food crops and livestock. This integration occurred around the beginning of the third millennium BC, and by 2500 BC, a composite cultural landscape had begun to emerge across the subcontinent.

The importance of Keeladi & TN's archaeological role

Sivagalai marks another key achievement for the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology (TNSDA), which gained prominence in 2017 after being entrusted with excavations at Keeladi.

Keeladi’s findings provided archaeological evidence for Tamil

Sangam-era literature, sparked public interest, while Sivagalai helped further establish Tamil Nadu’s role in reshaping global Iron Age chronology.

Keeladi: Politicisation & controversy

Keeladi, initially discovered by ASI’s Ramakrishna, has yielded

over 18,500 artefacts in ten seasons of excavations with the 11th phase set to begin anytime. Ramakrishna’s transfer to Assam in 2017, and his successor dismissing the third excavation phase, led to a public uproar and political debate. And the controversy sparked tensions between the BJP and DMK, particularly when Union Minister Gajendra Shekhawat, while justifying ASI asking Ramakrishna to rework on his report, demanded more evidence regarding Keeladi’s dating, despite international AMS reports supporting its antiquity.

Keeladi, one of the most important archaeological sites in South India, continues to be a focal point for political and scholarly disputes. Despite differing opinions, the site’s significance in pushing back the Sangam era remains undisputed. “There is a bias of the north against the south,” said Kurush Dalal, a Mumbai-based archaeologist. “However, the South is parochial, too. The fact that Keeladi pushes back the Sangam era is significant, but there is no evidence of urbanisation before this period.”

Human evolution revealed through

DNA analysis in TN

DNA analysis of samples collected from excavation sites in Tamil Nadu has provided groundbreaking insights into the region's ancient agricultural and culinary practices. These studies suggest that the early inhabitants of the area developed independent agricultural techniques, including the cultivation of various rice varieties and thinai (foxtail millet), which contributed to a diverse range of culinary traditions at least 2,500 years ago.

The research, which involved the analysis of 25 rice-related molecules from sites like Adichanallur and Sivagalai in Thoothukudi district, and thinai from Kodumanal, also highlighted evidence of ancient meat consumption. The presence of cholesterol in the pots suggests that the inhabitants consumed animal products, supporting this finding.

The analyses were carried out at the Ancient DNA Laboratory at Madurai Kamaraj University. Through this research, it was revealed that the ancient inhabitants used rice with ghee, beans, spinach, milk, cucumber, groundnuts, and coconut — foods that suggest a rich and varied diet. These findings are supported by references to culinary practices in Sangam Literature, including texts like Kurunthokai, Purananuru, Agananuru, and Porunararruppadai. Additionally, the study confirmed that the ancient people consumed boiled rice.

Human DNA analysis of skeletal remains from Konthagai and Adichanallur revealed a close genetic link to South Asian populations. Initial facial reconstructions have been attempted, and further reconstructions using at least ten samples are planned, with collaboration from a university in the UK.

Although the DNA reads from the urns at Konthagai and Adichanallur were limited, they provided enough information to show genetic similarities with the South Asian population in the 1000 Genomes Project, which encompasses five major ancestral groups, including West Eurasian (Iranian) hunter-gatherers and ancestral Austro-Asiatic people.

The TNSDA’s comprehensive

approach to archaeology

The TNSDA’s approach covers a wide range of periods, from Prehistoric to Medieval, across various regions of Tamil Nadu. This holistic approach aims to avoid bias and reconstruct the region’s cultural history by examining the sources and technologies behind artefacts, especially in the absence of local copper and tin deposits.

Rajan explained that TNSDA's long-term goal is to complete a comprehensive cultural history of Tamil Nadu within the next 20 to 25 years through continued excavations, scientific dating, and interdisciplinary research.

By excavating 53 sites, the TNSDA has made significant strides in understanding Tamil Nadu’s ancient history. They have uncovered over 19,000 artefacts, revealing a rich and complex cultural landscape. Scientific methods like Accelerator Mass Spectrometry have played a crucial role in revising the timeline of writing systems in the region, with the Brahmi script being in use as early as 490 BC at Porunthal and 480 BC at Kodumanal.

As excavations continue, the TNSDA’s work continues to reshape global and regional understandings of ancient Indian civilisations, with Sivagalai’s early Iron Age dates being a key piece of this puzzle.

Images: DH Photos/ E T B Sivapriyan/Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology

DH Video: Adithyan P C & Rajath Sharma