Himalayan overload

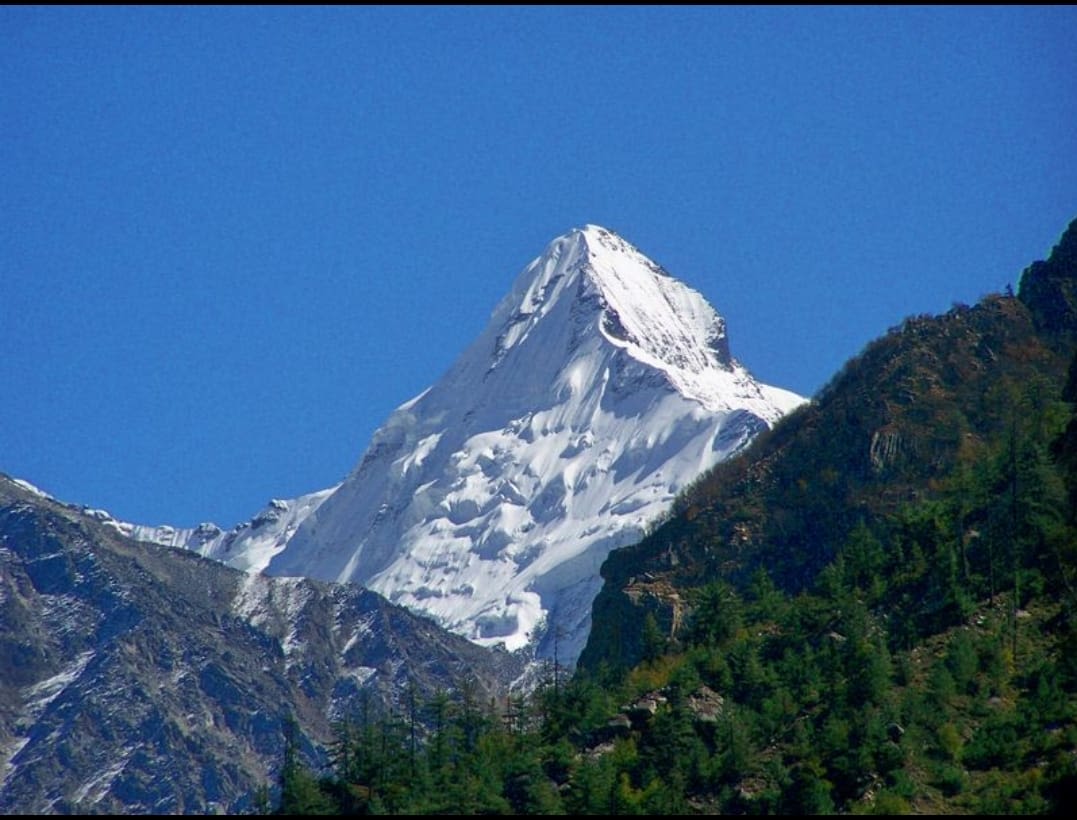

Tourist arrivals have multiplied sixfold in two decades. As crowds swell, so do the challenges, from traffic gridlock to the strain on a fragile Himalayan ecology.

Concept by: Shobhana Sachidanand

Words by: Sumit Pande

Illustrations by: Sajith Kumar

If you are a Hindu from the sun-scorched plains of India and you desire…to perform the pilgrimage to the age-old shrines of Kedarnath and Badrinath, you must start your pilgrimage from Hardwar [Haridwar] and,…you must walk every step of the way from Hardwar to Kedarnath and, thence, over the mountain track to Badrinath, barefoot.

The man-eating leopard of Rudraprayag

Jim Corbett

Ahundred years ago, in 1926, ace hunter and conservationist Jim Corbett chased a human-eating leopard that prowled in the Alaknanda valley for eight years and preyed on pilgrims trudging along the roads that were ‘narrow and rough and had never had a wheel of any kind on them.’

Fast forward to 2025. In the three months after May, since the portals of Badrinath and Kedarnath were thrown open, more than 41 lakh pilgrims riding 10 lakh vehicles have already travelled on the Char-Dham route, according to data from the Uttarakhand Department of Tourism.

The trek to the higher reaches of the Himalayas, a journey towards renunciation that once took months to complete, can now be accomplished within a week in fuel-guzzling SUVs driven through the ever-expanding maze of metalled roads.

For those who can afford to shell out a few lakhs more, there is always the chopper facility, which can, in a matter of two to three days, bring instant deliverance for the worldly wise.

The surge of Saawan

To this multitude of salvation seekers, add another three to four crore kanwarias, the Shiva devotees who, during the month of Saawan, throng Haridwar and go further up to Rishikesh, where the holy Ganges gurgles down the final set of rapids and cataracts to enter the Indo-Gangetic plains.

Rishikesh, the Yoga capital of the world, is home to 3 lakh people. Apart from the millions of registered Char Dham yatris, non-pilgrim tourists en route to the hills also have to cross the temple town nestled between two hills, and as many arterial roads: One that runs through the residential areas, and a bypass that skirts around the city centre.

Tourism 2024: Pilgrimage reigns, leisure expands

Total footfall: 9.5 million visitors

Slight rise from 2023; steady recovery and saturation visible

Pilgrimage highlights

Haridwar: 34.9M

Kedarnath: 1.65M

Badrinath: 1.77M

Hemkund, Gangotri, Yamunotri: Around 1.24M combined

Leisure hotspots

Mussoorie: 1.47M

Nainital: 1.02M

Rishikesh: 758K

Tehri Lake tourism: 5.07M

Corbett NP: 362K

Uttarakhand: Sacred peaks, surging footfalls

20 years of tourism data (2000–2020)

Visitor growth

Tourism nearly tripled

in two decades

📈 2000: 11.1M → 2019: 39.2M

📉 2020: Due to Covid-19, visitor numbers dropped sharply to just 7.8M, the lowest in years

Pilgrimage surge

Char Dham overwhelmed by a surge in spiritual traffic

Haridwar: 5.3M → 21.7M (2000–2019)

Kedarnath: 154K → 999K (2015–2019)

Badrinath: 366K → 1.24M (2015–2019)

Hill station strain

Visitor load doubled

Mussoorie: >2.7M/year (2015–2019)

Nainital: 417K → 933K (2002–2019)

Tourist peaks strain resources and heighten landslide risks in the hilly areas

Eco-tourism spike

Parks have been feeling the pressure

Jim Corbett National Park in Nainital, Uttarakhand: 65K → 283K (2002–2019) Wildlife zones are now peak-season hotspots.

The Covid-19 reset

Tourism collapsed in 2020

Haridwar: 21.7M → 4.0M

Kedarnath: 999K → 135K

Mussoorie: 3.02M → 1.01M

The road ahead

Time for smarter tourism

• Spread footfall across seasons

• Limit vehicles, regulate construction

• Improve waste management

Tourism rebounds

2021–2023 at a glance:

Uttarakhand’s tourism bounced back post-Covid-19 — from 20M in 2021 to nearly 60M in 2023

Spiritual sites led the surge: Kedarnath jumped from 243K to 1.96M; Haridwar tripled to 37M

Hill towns followed suit: Nainital more than doubled (326K → 784K), Mussoorie neared 1.5M

Wildlife parks saw steady gains — Corbett grew from 294K to 333K

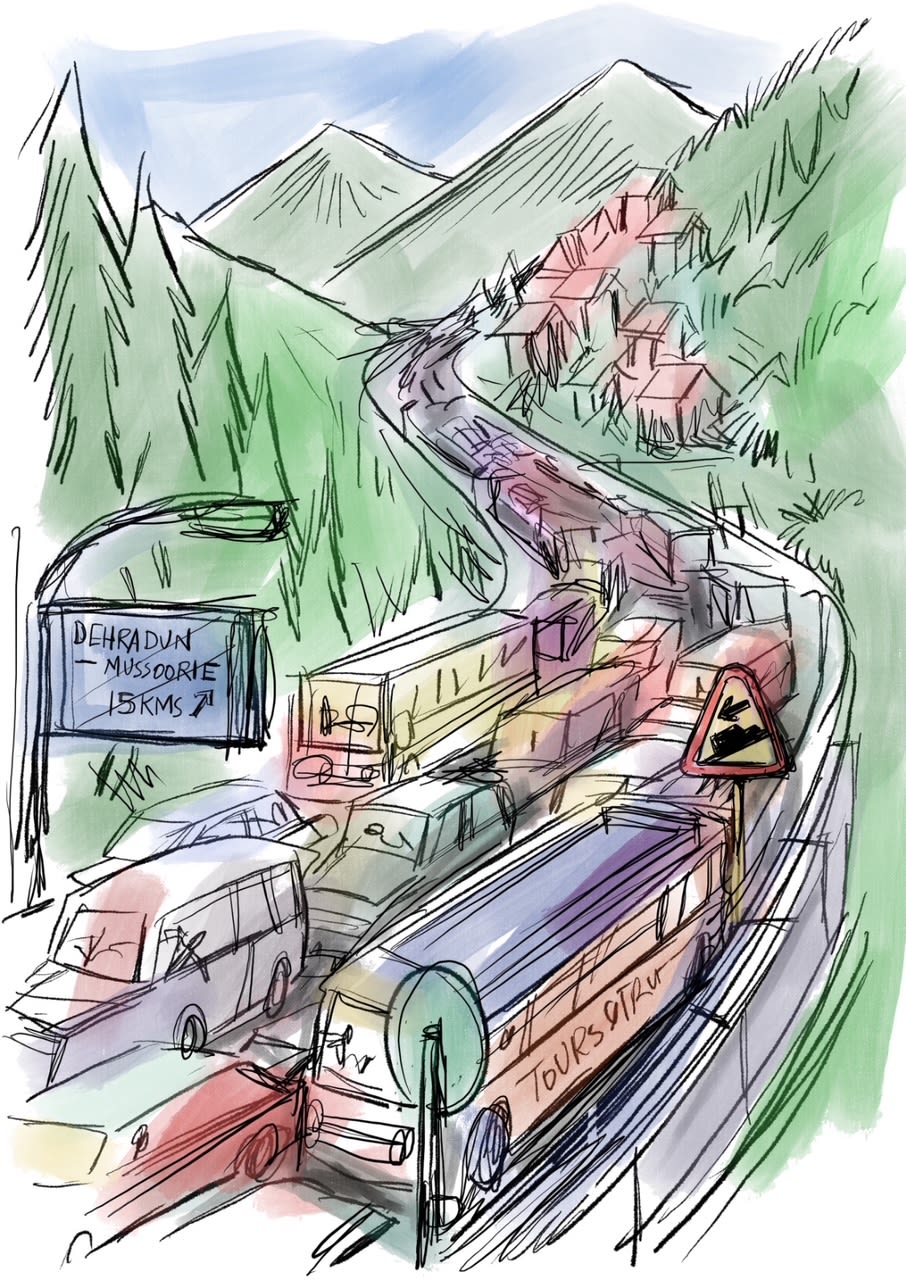

Choked arteries, clogged towns

In peak season and on most weekends now, vehicles pile up at bottlenecks where eight-lane highways, bringing a legion of cars from Delhi and adjoining areas, shrink upon touching the hilly terrain. This results in hours of traffic jams, heightened air pollution, and chaotic scenes at roundabouts. Rishikesh today is a far cry from the salubrious station that once attracted sages and stars alike — from Swami Vivekananda to the Beatles.

“Rishikesh, Haridwar, and Dehradun form a triangle. A journey from one to another would generally take 45 minutes to 1 hour. Now you can find yourself stranded for hours on end,” says Manmohan Bhatt, a local journalist.

That is precisely not what Sanjeev Vatsalya bargained for when he left his well-paying job in the US to build a home for himself here in 2002. Uttarakhand, comprising the hill districts of Kumaon and Garhwal divisions and the Tarai belt of Haridwar and Nainital, had just been carved out of Uttar Pradesh.

The newly crafted hill state offered an attractive second-home option to many. Two decades later, the situation has reached such a pass that locals in Rishikesh often dread venturing out.

“It would take 45 minutes to 1 hour for my children to reach school, a distance of 5 to 6 kilometres,” Vatsalya says. Unable to tolerate any more of the gridlocks, snarls, and congestion, he and his family moved to Rajasthan.

Kathgodam’s crowded corridor

About 300 kms southeast of the capital, Dehradun, is the second major gateway to the Uttarakhand hills — Kathgodam, which was once a forest department depot and also the last point of rail connectivity for the Kumaun division. For tourists visiting Nainital, Almora, or the upper reaches like Pindari Glacier, Kathgodam is the point of entry.

Unlike the pilgrimage sites of the Gharwal hills, the temples in the Kumaon hills are dedicated mostly to local deities. Except for the Kailash Mansarovar yatris, who take this route (and their numbers are in thousands), religious tourism here has been significantly less compared to the middle- and high-income travellers who want to stroll on the Nainital Mall abutting the emerald-green lake.

Pilgrimage 2.0:

Jageshwar & Kainchi

Post-Covid, the profile of the tourists visiting the Kumaon belt has changed in the last five years, as two major pilgrimage spots have started to attract lakhs of yatris.

The first is Jageshwar — a group of 125 post-Gupta and pre-medieval Shiva temples interspersed over a 7 km stretch amidst towering deodars. Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2023 visit to Jageshwar, the footfall of pilgrims in this once secluded sanctuary, 35 kms from Almora, has risen exponentially.

The Kainchi Dham, 15 kms from Nainital, is the second destination that is drawing huge crowds. The temple, which derives its name from the approach road with multiple hairpin bends that appear like a pair of scissors from the hilltop, was established as a small ashram in the mid-sixties by Baba Neem Karauli, a mystic saint who frequented the area.

Now, Kainchi, on one of the main arterial roads that connects Delhi and Lucknow with the remote towns and villages in the hills, is a traffic nightmare. There is hardly any parking space to accommodate thousands of private vehicles that arrive from as far as Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat.

Local economies tend to benefit from a surge in tourist inflow. But when it becomes a problem of plenty, the populace not directly linked to the tourism industry begins to feel the resource crunch as the cost of living shoots up.

Social scientists call it overtourism. In Uttarakhand too, there appear to be telltale signs of precocious tensions and fault lines emerging between the locals and the visitors, between the domiciles and the outsiders.

In an incident reported from Mussoorie in the first week of June, despite a police escort, a senior citizen who fell ill could not make it alive to the nearest hospital due to traffic congestion. It took almost an hour to reach the medical facility that was just 4 km away.

On June 9, a 40-year-old man from Nainital district died when the ambulance transporting him to the hospital got stuck in a traffic jam near Kainchi Dham. The journey to the hospital, which generally takes two hours, took almost 5 hours.

The same day, a bunch of undergraduate students from Kumaun University, on their way to Nainital to appear for their semester exams, were stuck in a traffic congestion near Kainchi. They could not make it to the examination centre on time and missed their paper.

“The traffic management is so poor that on some days we are not able to visit the local market, which is just 3 km from my house on a two-wheeler,” says Sanjeev Bhagat, who runs a shop on Bhimtal-Bhowali road.

Tourism’s paradox

Ironically, the hotel industry, which should benefit the most from the surging crowds, is far from satisfied with the current state of affairs.

“Traffic congestion has led to tourists being stranded hours on end,” says Praveen Sharma, a Nainital hotelier who says many hotels in Nainital, Kausani, and Mussoorie reported low occupancy during peak season.

A majority of the visitors are religious tourists who prefer affordable lodges over hotels, or sometimes spend the night in their vehicles.

“Big travel operators in Kolkata and Mumbai have started to dissuade travellers from visiting Uttarakhand during summer as tourist groups have reported being stuck in jams for hours on end,” adds Ratan Singh Aswal, a Dehradun-based social activist.

The tipping point

The situation in popular tourist destinations in India, apart from Uttarakhand, has also reached a tipping point. In 2024, 1.8 crore tourists visited Himachal Pradesh, which has a population of 75 lakh. During peak season, about 40,000 vehicles enter Himachal Pradesh every day. Last week, the Supreme Court, while hearing a petition, on deteriorating ecological and environmental conditions in Himachal Pradesh (HP), observed, “the day is not far when the entire State of HP may vanish in thin air from the map of the country.”

Down south, Munnar in Kerala, this year experienced a sudden rush of tourists who rescheduled their trip during the summer months after the Pahalgam attacks, leading to massive traffic jams.

Apart from the ecological impact, overtourism in Kodagu and Chikkamagaluru in Karnataka, is facing demographic changes. In Kodagu, Kodavas are slowly migrating towards Mysuru and Bengaluru, selling their coffee estates and sprawling bungalows to people who are not from the region.

Madakeri-based environmentalist Thammu Poovayya says a labour shortage is forcing many locals to sell their property to outsiders. “Over the last two decades, nearly 8% to 10% of the population has changed in Kodagu. The modern hospitality set-up is the root cause of all the landslides and flooding in Kodagu,” he says.

He says that the district administration and government seem not to have learnt any lessons from the recent natural disasters.

The situation is no different in the neighbouring Chikkamagaluru district. Under the guise of eco-tourism, the fragile hill ecosystem is being destroyed to create tourist amenities. Environmentalist Girish D V says promotional activities are being carried out without conducting any scientific study on the carrying capacity of each location.

He says places like Mullayyanagiri, Baba Budangiri and Devaramane are overexploited, and if immediate measures are not taken, these hills will witness catastrophic tragedies.

Earlier this year, the Madras High Court had to issue an order restricting the number of tourist vehicles entering Ooty and Kodaikanal between April to June.

A sinking feeling

The United Nations World Tourism Organisation defines overtourism as “the impact of tourism on a destination, or parts thereof, that excessively influences perceived quality of life of citizens and/or quality of visitors' experiences in a negative way.”

Overtourism comes with an ecological cost attached. The state and individuals create additional infrastructure to cater to the burgeoning traveller.

In January 2023, a quarter of the total 4,000 houses in Joshimath, the winter abode for the Badrinath deities in Chamoli district of Garhwal, Uttarakhand, developed cracks. Some scholars have attributed the land subsidence in this tremor-prone, fragile Himalayan plate to tunnel boring in the Tapovan-Vishnugad Hydropower Project that “passes through the geologically brittle area just below Joshimath.”

The National Disaster Management Authority, in its preliminary report to the National Green Tribunal, says Joshimath has exceeded its carrying capacity by far and the area must be declared a “no new construction zone.”

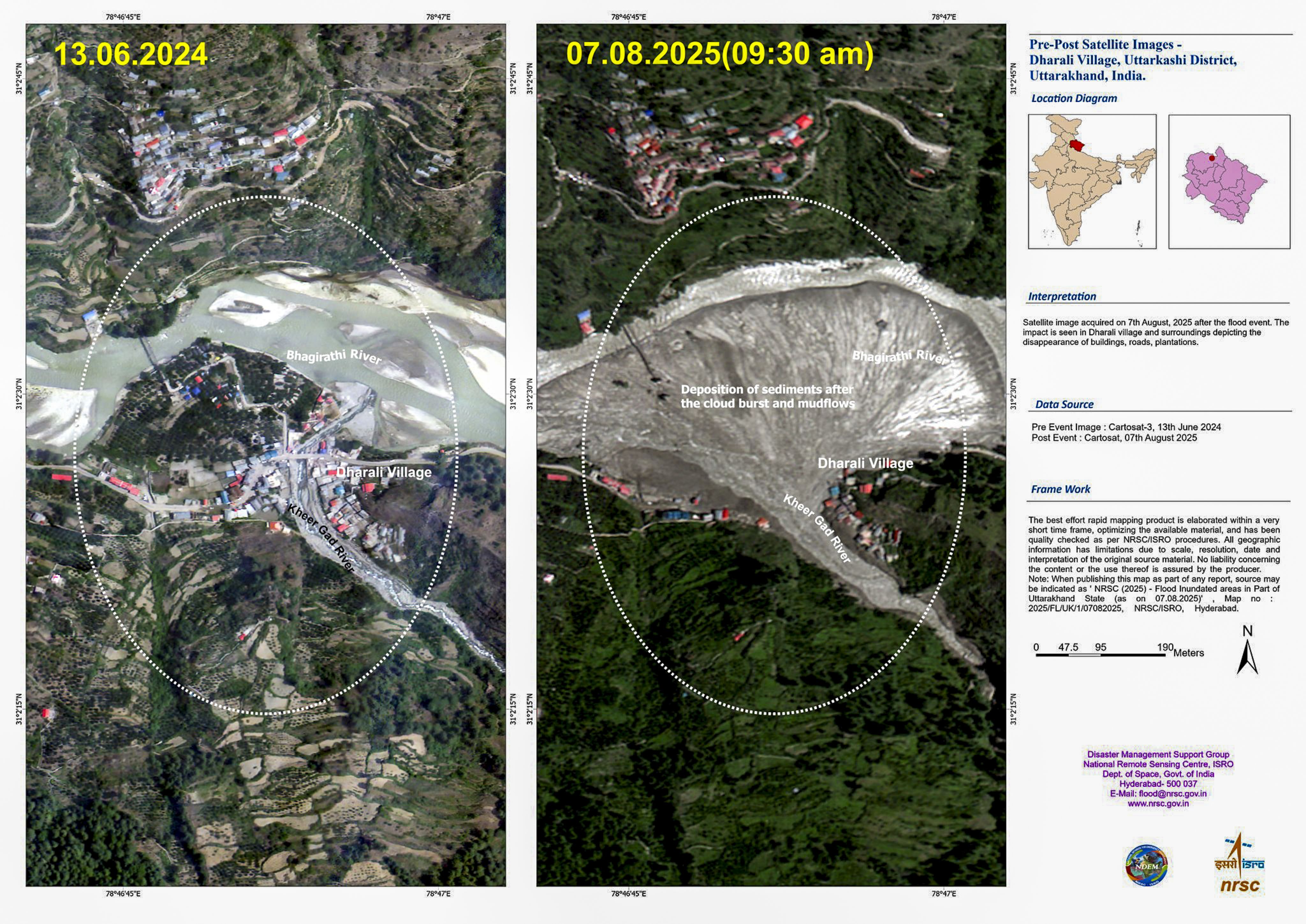

The ecological cost of overtourism and infrastructure development has been mounting over the years. In 2019, Goa generated 300 tonnes of solid waste daily. The Hindu Kush Himalayan Range, extending from Afghanistan to Myanmar, has registered a significant decline in the annual snowfall that feeds all perennial rivers in the region. Some glaciers have shown an almost 50% drop in snow depth due to the temperature rise. Glacial Lake Outburst Floods GLOF events, like the Kedarnath, are on the rise.

Similar apprehensions were being expressed of the overcrowded Mussoorie. Taking suo motu notice of media reports on the ecological threats to the ‘Queen of Hills’, an NGT-appointed panel has recommended regulating the heavy tourist influx. Acting on the report, the state government just last week made it mandatory for all Mussoorie-bound tourists to register online.

Interestingly, a day earlier, the Road Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari, in response to a question in the Rajya Sabha, said the Delhi-Dehradun Expressway, which would reduce the travel time between the national capital and the Uttarakhand capital to 2.5 hours, would be operational in October.

“What is the point of all this? If cars and buses are going to arrive in hordes, where will you park them? Both Dehra and Mussoorie are already bursting at the seams,” says Col Anup Nautiyal, a Dehradun-based social worker.

The state government is aware of the tensions and strains generated by overtourism. “We are also trying to see that tourist travel is evenly spread across the state and not confined to specific locations. For that, other tourist spots are being developed,” says Dheeraj Singh Garbyal, Tourism Secretary, Uttarakhand.

As in the case of Mussoorie, the carrying capacity of other major hill stations is being assessed.

Developing alternative infrastructure takes time, especially in landslide-prone hills. The widening of roads need not necessarily ensure round-the-year mobility. Perhaps what India needs is a national policy on sustainable tourism.

(With inputs from Pawan Kumar H in Hubballi.)

Global tourism trends

Across Europe, the summer of 2025 witnessed widespread demonstrations against overcrowding in tourist destinations.

In Barcelona, locals sprayed tourists with water guns. In the Spanish island of Mallorca, residents demanded an end to ‘mass-tourism’. In Italy, annual flooding by cruise goers was decried on social media and the streets. In Paris, Louvre staff protested the overcrowding of the museum’s galleries. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos had to shift his wedding reception out of Venice as protestors sought to “save Venice from Bezos.”

Tourism pressure:

Barcelona’s lesson for India

Tourists

vs locals

Barcelona: 30M tourists, 1.6M locals→ 18:1

Goa: 10.4M vs 1.46M → around 7:1

Leh: 0.52M vs 31K → around 17:1

Both face seasonal population flips.

Pressure on ecosystems

Barcelona: Hotel boom, rental surge, water and waste stress

India: Landslide deaths in Wayanad, clogged hill towns

Unregulated growth harms fragile landscapes.

The local pushback

Barcelona: Anti-tourism graffiti, top public grievance

India: Mussoorie & Goa locals protest illegal rentals, crowding

Loss of space and culture stirs resentment.

Policy

action

Barcelona: Hotel ban, rental licensing freeze

India: CRZ limits, permits in Kedarnath, Kodaikanal

India’s response is reactive; enforcement lags.

Identity at risk

Mass tourism alters local character.

Sacred towns in India lose sanctity.

Barcelona’s old quarters face cultural erasure.

Tourism threatens both heritage and habitability.

Lessons from Barcelona

Proactive caps, zoning rules, and local-first policies.

Transparent data guides planning.

India needs better forecasting and people-centric tourism.

Restrict to protect; let places breathe.

The need to diversify India's tourism narrative

India’s tourism boom is testing its hills, heritage, and habitats. Without sustainable policies, the country risks losing what makes it special, writes Sundeep Bhutoria

The summer of 2025 brought more than just seasonal heat to India — it exposed a simmering crisis that is reshaping the country’s tourism economy. Tourism in India is undergoing a seismic shift. What was once a largely seasonal purpose-driven activity — whether for pilgrimage, leisure, or heritage — has now evolved into a persistent, all-year phenomenon. In many regions, especially those known for natural beauty and historical charm, the line between promotion and exploitation is wearing thin.

This surge is not without cost. The very cultures, ecosystems, and community rhythms that attract tourists are now at risk of being eroded.

At the heart of this transformation lies a policy vacuum. India lacks a unified and enforceable national tourism framework that prioritises sustainability. Local authorities are often under-resourced, reactive, and politically constrained.

In Swiss Alpine towns, in contrast, carrying capacities are non-negotiable. Visitor caps, zoning restrictions, and dedicated tourism police units ensure that tourism never overwhelms the host environment.

The Indian response, by comparison, remains piecemeal. India must diversify its tourism narrative. National and state tourism boards need to promote lesser-known destinations.

Second, mobility models must be reimagined. Hill stations should invest in clean, efficient, and scenic public transit — electric buses, ropeways, and pedestrian paths are vital. Parking zones should be set up at entry points, and last-mile mobility solutions should be eco-sensitive and scalable.

Third, local communities must be empowered. Tourism revenue should be ring-fenced for local infrastructure: Healthcare, fire services, water systems, and waste management.

Fourth, India needs a functional tourism police system. These units should help maintain public order, protect cultural sites, and support travellers while upholding community norms.

Most importantly, the mindset of the Indian traveller must evolve. Respect, not entitlement, should define the tourist ethic.

India’s hill stations are repositories of history, literature, and cultural resonance. To let them buckle under the weight of tourism would not just be an ecological loss — it would be a civilisational mistake.

(Sundeep Bhutoria is a columnist and author who writes on environment, education, wildlife, and conservation)

Data source: Uttarakhand Tourism Dept (2000–2020); Uttarakhand Portal; UN World Tourism Organisation Report on Overtourism; United Nations Statistics Division; Char Dham Yatra Data

Images: PTI, Reuters, Satellite images released by @isro via X (formerly Twitter), DH File Photos, iStock, Sanjeev Bhagat, Ajay Ramola

Videos: Indo-Tibetan Border Police

On-screen video source: Social media | unverified origin

(Disclaimer: Video used for news reporting in public interest; source untraceable despite efforts. Contact us for credits.)