Beyond headlines:

The endemic

of rape in India

The horror of sexual violence has ignited the country again, forcing it to confront a fundamental, ugly truth

TRIGGER WARNING // Rape, Sexual Violence

On December 16, 2012, a 23-year-old student was brutally assaulted and gang-raped in a moving bus in Delhi, the national capital. She and her friend were returning from a movie, when six people, including a juvenile, tortured and raped her and thrashed her friend, before leaving them on the side of the road to die.

The 'Nirbhaya' case, as it came to be known, shook the nation’s conscience. The hope was that it would herald a new era.

Cut to 2024, India is again on the boil after a 31-year-old trainee doctor was found dead in Kolkata’s R G Kar Medical Hospital. The autopsy showed that she sustained horrific injuries before death, and the report read, "Death was due to effects of manual strangulation associated with smothering ... manner of death—homicidal. There is medical evidence of forceful penetration/ insertion in her genitalia—possibility of sexual assault."

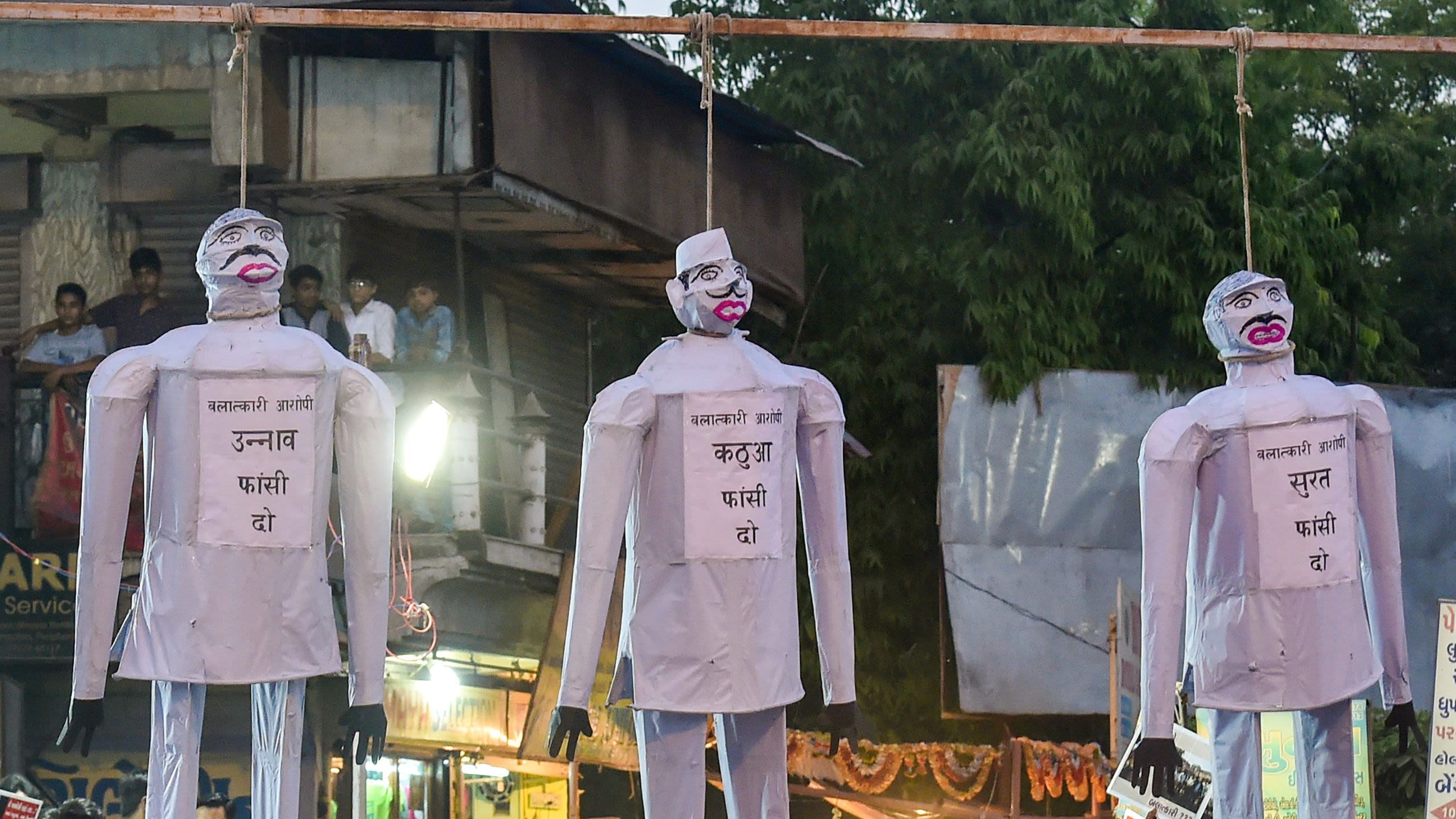

In the 12 years between the Nirbhaya incident and the R G Kar case, the female body has remained a site of blood-curdling savagery, as evidenced in the Unnao rape case, the Kathua gang-rape, the Hathras incident and so many, many more that we didn’t even hear about.

"As a society we are complacent and have momentary outbursts of emotions that last as long as the next breaking news comes forth," Supreet K Singh, the co-founder of women's safety non-profit Red Dot Foundation, told DH, adding that it took India 12 years to again sit up and say, "We have a problem."

Even as the urban youth continue to squabble over 'not all men' and 'yes all women', the ubiquity and constant threat of sexual violence has instilled a sense of unshakeable fear in Indian women.

ALARM BELLS RINGING

Numbers speak a thousand words

31,516 cases. 31,982 victims. 86 rapes a day.

Those are the latest numbers from India, as per 2022 data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). While they represent a mere fraction of the 4,45,256 registered cases of crimes against women in the same year, they depict what seems to have become a new, grim normal for the country, which has averaged well over 30,000 rape cases a year since 2013, dipping below that level only in 2020, during nationwide lockdowns to contain the spread of Covid-19.

Indeed, long-term data from NCRB shows a steep, steady and alarming rise in annual rape cases across India, with some states eclipsing others in terms of the incidence of sexual violence. The interactive map below captures the same.

The graphic below on rape statistics shows the monstrous scale and extent of the malaise, despite most cases going unreported.

Although most rapes are reported in rural areas, urban India accounts for a significant number, with the national capital having earned the moniker of 'rape capital' owing to the disproportionately large number of cases registered there. The illustration below shows the total number of registered rape cases across major cities, since 1974.

RAPE CULTURE

An underlying malaise

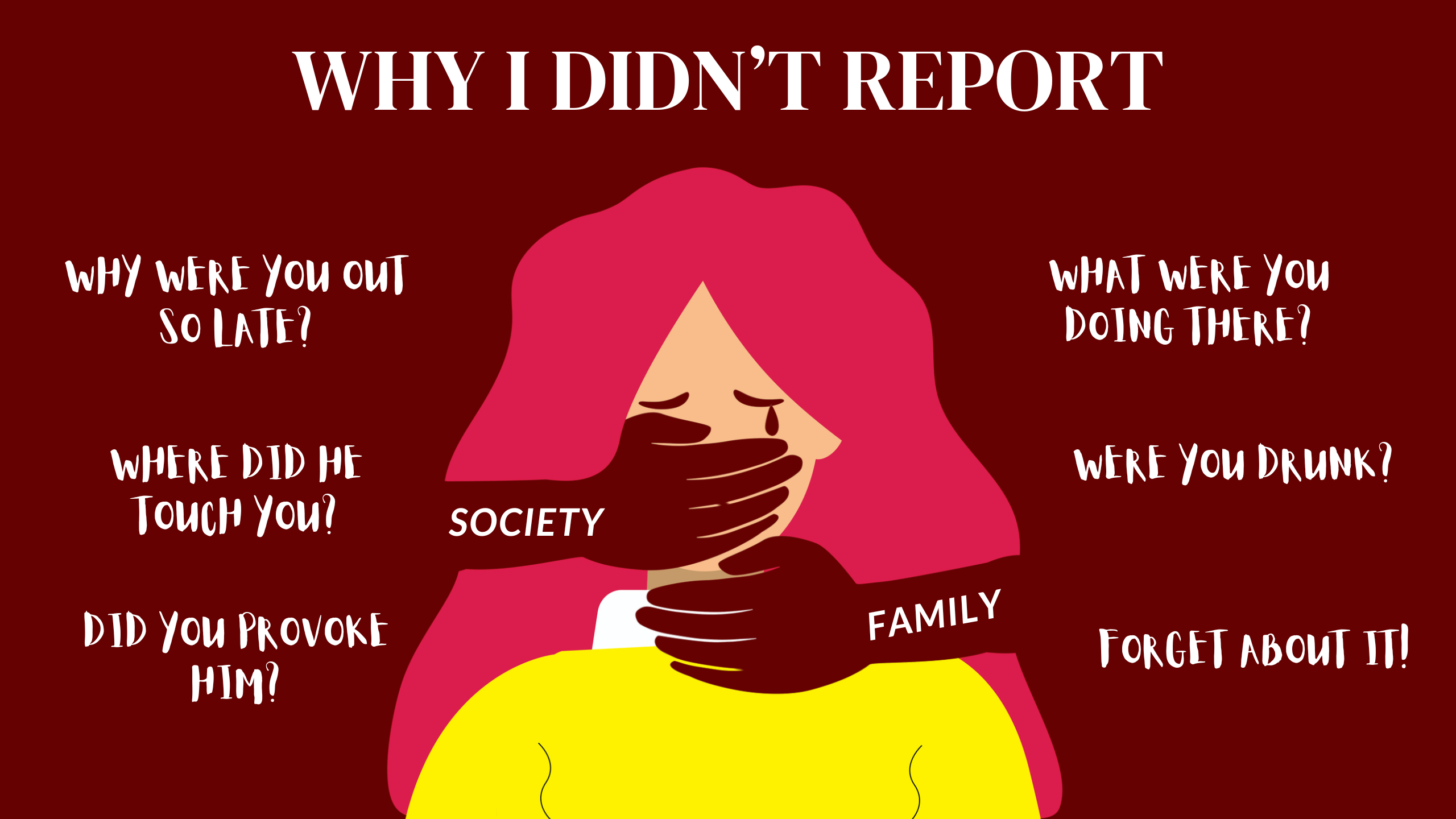

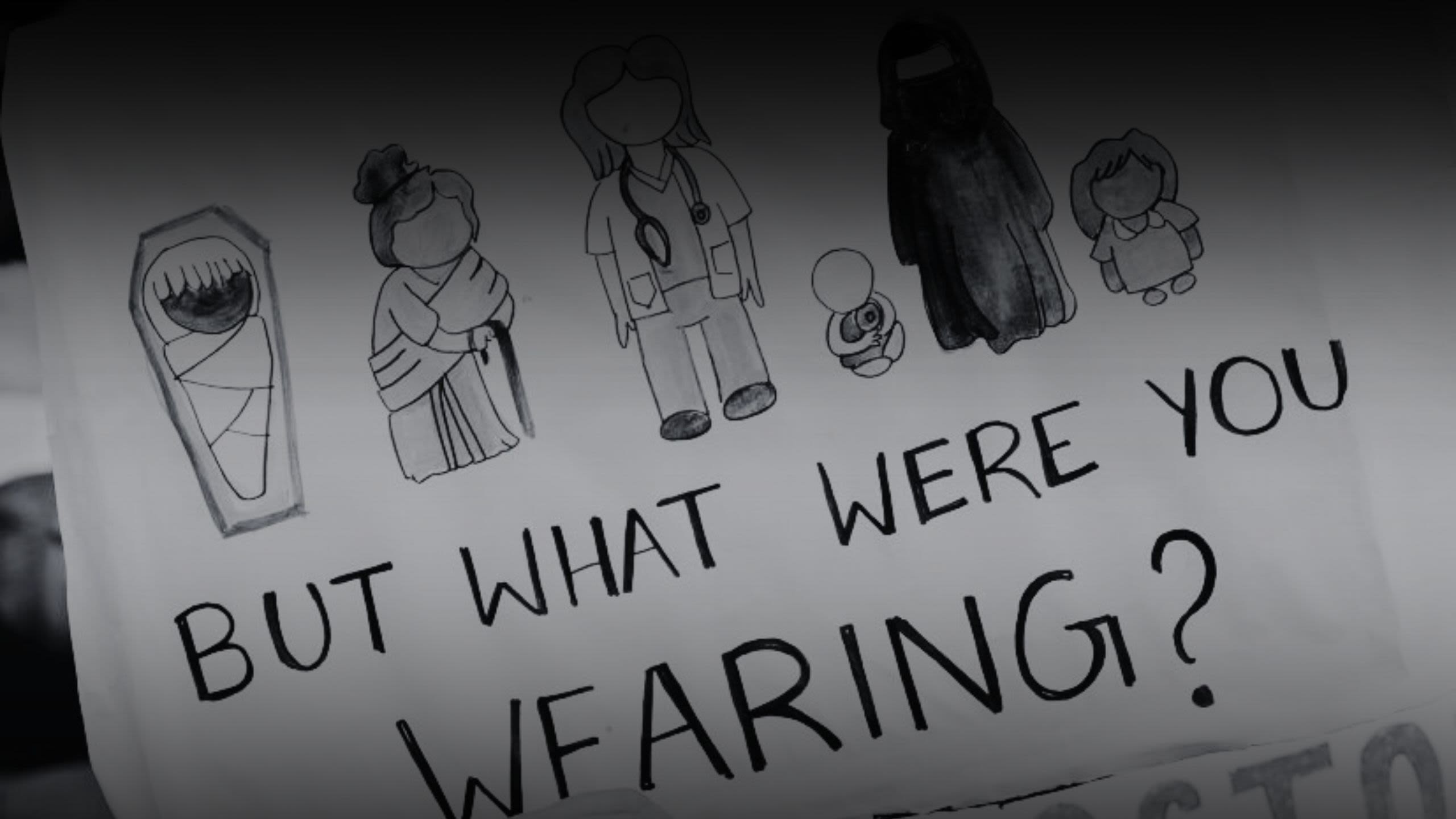

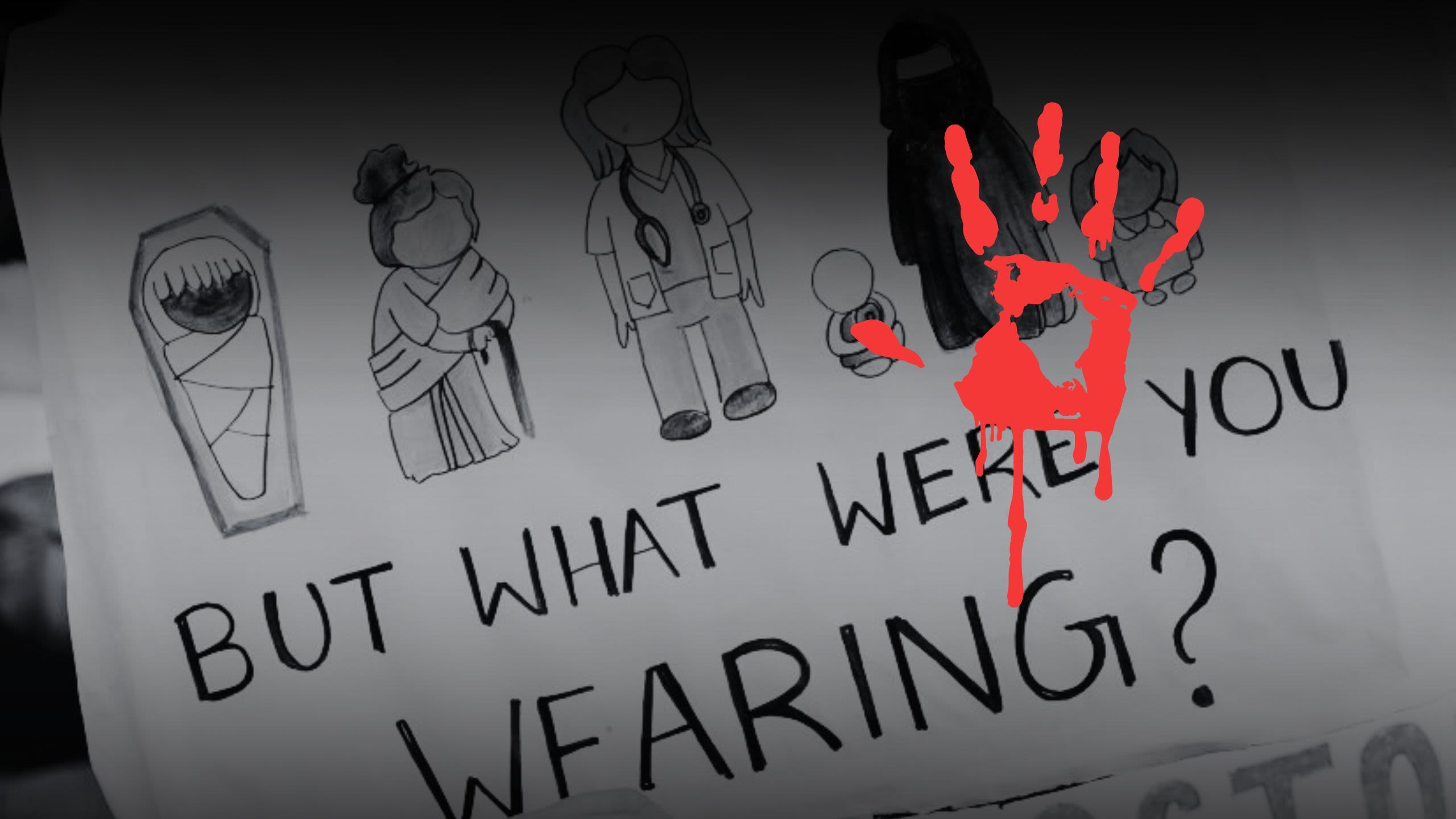

While there has been a mammoth increase in the number of crimes reported against women in India over the years, 99.1 per cent of sexual assaults in the country still remain unreported, as per a 2022 analysis.

Even when the majority of sexual violence cases against women remain unreported, the ones that do get reported are often trivialised.

"No man on his first attempt goes and rapes somebody. They start with smaller incidents like sexual harassment, teasing, molesting and then their confidence gets built as society and police don’t take these cases seriously. Even if one goes on to report them, they usually don't get support because these are considered to be small incidents."

While daily cases of rape reported across the country receive little to no attention, it is usually after atypical sexual crimes in major cities—like the one in Kolkata's R G Kar Hospital—that civil society mobilises.

Enduring class divides and deep-rooted inequalities perpetuated by the caste system add to the complexity of the problem, with women from poor and lower caste backgrounds being at greater risk of rape and sexual assault. In fact, there was a 45 per cent increase in reports of rapes of Dalit women between 2015 and 2020, and women from Scheduled Tribes (STs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) remain disproportionately affected by sexual violence in comparison to women who are not marginalised by caste or tribe.

Even as protests related to individual cases continue for days, a woman is raped every 16 minutes in India, while several other similar crimes never make it to police records.

Rape cases that do make it into records, meanwhile, rarely see alleged rapists punished: conviction rates ranged between 27-28 per cent between 2018 and 2022, essentially indicating that roughly three of four people charged with rape walk free.

Given the extent of underreporting, the scale of crimes against women, and dismally low conviction rates, isolated protests are not enough, say organisations helping survivors.

"Creating awareness and speaking of such inhumane acts is the first step, but sadly, in most cases, it ends there until another crime occurs and results in a protest. The solution to this does not lie solely in a protest but also in our day-to-day encounters, words and actions, how we influence people around us, how we utilise our right to expression, how sensitive we are towards a fellow human being etc."

Some of the main reasons behind why women overwhelmingly decide not to report incidents of sexual violence against them are: the attitude of the police, a desire to avoid revisiting traumatic memories, and lengthy court procedures.

"The attitude of law enforcement plays a critical role in this decision-making process. Authoritarian personalities within the police force, shaped by rigid and patriarchal societal structures, can appear unempathetic and even hostile toward victims. This often results in victims perceiving the police as unsupportive or dismissive, further dissuading them from coming forward. Dehumanization processes within the police force can exacerbate this issue, where victims are subconsciously viewed as less human, leading to indifferent or even harsh treatment."

Rape culture, by trivialising sexual violence and cementing depraved attitudes, creates a pervasive environment wherein women are often discouraged from or unwilling to report such crimes.

WHAT IS RAPE CULTURE?

Rape culture refers to an environment wherein rape is prevalent and sexual violence has been normalised since there are no social constraints that discourage sexual aggression and/or arrangements that encourage it. Such a milieu is understood to be an extreme manifestation of widespread societal misogyny that normalises men’s aggression towards women.

"All of these (sexual abusers) boys are raised in homes that encourage this rape culture and uphold it … The same man is abusing his wife, sister, or mother at home and then he is coming out."

The very fact that rape as a crime—separate from larger categories such as violent crime, theft, riots, etc.—came into national records only in 1974, 21 years after the first 'Crime in India' report of 1953, is perhaps a glaring example of the normalisation of sexual violence that is characteristic of rape culture.

There is no doubt that rape was prevalent in India before 1974—the infamous 1972 Mathura custodial rape case, which became a watershed moment for the country’s rape laws, is a case in point.

This incident not only sparked one of the first public protests against rape in India but also paved the way for the passage of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1983, which marked the first significant change to rape laws since they were first codified in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) in 1860.

Meanwhile, a separate category for 'Crime against Women' under different heads was added to the government's annual 'Crime in India' report in 1992, 39 years after its first edition.

Deep-rooted rape culture in India can also be seen in the reluctance to criminalise marital rape, a subtle indication that society expects women to tolerate sexual abuse by their husbands.

It is noteworthy that an average Indian woman is 17 times more likely to face sexual violence from her husband than from others.

Despite this, India is among the handful of countries worldwide—including Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, UAE, Saudi Arabia, and some sub-Saharan African countries—where marital rape has still not been criminalised or is explicitly/implicitly excluded from the scope of the law.

That being said, the Supreme Court in May 2024 issued a notice to the Union government on a batch of pleas challenging the marital rape exception under the new criminal laws.

The apex court was also slated to begin hearing a batch of pleas challenging immunity granted to husbands under Section 375 of the IPC from August 13, 2024. However, at the time of writing this on August 29, the hearing had yet to commence.

While rape culture often begins at home, it is provocatively promoted through ‘art’ as well. Hindi and regional cinema that glorify violence against women and songs that objectify the female body are day-to-day expressions of toxic masculinity and misogyny prevalent in Indian society.

Art influences worldviews and ideologies, and while not every member of an audience may get influenced by rampant misogyny in cultural productions, the very peddling of these attitudes in the name of art serves to perpetuate an already entrenched mindset.

"After Shah Rukh Khan said 'K…K...K…Kiran', almost everybody wanted to say 'K…K...K…Kiran'," Supreet told DH as she explained how fans get influenced by their favourite artists.

However, she also batted for changes to the education system to help audiences navigate through films or content that promote misogyny and not see them as life lessons.

“We need art appreciation courses as a mandatory part of the education system so that the youth are equipped with how to consume content that sometimes glorifies toxic relationships under the garb of love, mostly enacted by superstars.”

The entrenched nature of rape culture is also evident in the everyday use of language: phrases such as "she asked for it", "boys will be boys", or use of "rape" to describe resounding victories or bitter defeats are more commonplace than one would believe and are often downplayed and overlooked in the name of 'humour'.

Does porn perpetuate rape culture?

The main accused in the R G Kar case, Sanjoy Roy, was reportedly a pornography addict. It was also reported that there were searches for the victim's video on porn sites. So, how big a role does porn play in perpetuating rape culture?

Over the years, access to porn has become easy in India, with increasing internet and smartphone penetration, and low data costs. Despite government attempts to block porn sites, porn remains just a click away today. But, does the consumption of pornography translate to sexual violence?

"Evidence for a causal relationship between exposure to pornography and sexual aggression is slim and may, at certain times, have been exaggerated by politicians, pressure groups and some social scientists," a paper on the matter states.

Another study posited, "An association between pornography use and nonsexual violence seems to exist, although the causality of this association remains unclear. Heterogeneity of results exists regarding the association between pornography use and intimate partner sexual assault and coercion: some studies have failed to demonstrate this association, while others have observed it partially or significantly. Contradictory results have also been observed when examining the association between pornography use, rape myths, and other beliefs/attitudes. The main limitation is the heterogeneity in the conceptualization of both constructs (pornography and violence)."

However, another study on teenage dating violence found that "adolescents acquire information about sexual roles and behaviors through sexual media consumption and observing relevant models. Specifically, with increasing exposure to degrading and/or aggressive depictions of sexual relationships, these types of scripts are more likely to be activated and applied in real-life dating relationships."

The opinion seems to be that a simple causal link between pornography in general and sexual harassment, abuse, and assault cannot be drawn.

Yet, consumption of violent, extreme pornography nonetheless points to a degree of perversion that exists within society, which was also evidenced when video clips of former Hassan MP Prajwal Revanna's alleged rapes were circulated and became readily available online.

AND JUSTICE FOR ALL

Need of the hour

While uprooting rape culture is the goal, it is a long journey for which widespread systemic changes are imperative.

India's three new criminal laws, which replaced colonial-era codes and came into effect on July 1 this year, did introduce some changes for the prosecution of crimes against women. These changes were touted as being indicative of a growing concern for women's safety.

However, lawyers DH spoke to pointed out that extant inadequacies in the criminal justice system have been exacerbated by the implementation of the new criminal laws, which have not been accompanied by other necessary reforms.

“In the criminal justice system, you can’t merely tinker with legislative reform: you have to address the elephants in the room—police reform and judicial reform. You do nothing on those fronts, and you simply change a few sections of the law and think you’re going to revolutionise justice. It doesn’t work like that.”

While more stringent laws may now exist on paper, effective prevention and prosecution of crime is not possible without larger reforms across the board.

“I don't believe that introducing more stringent punishments—death penalty for rape for example—will necessarily stop or reduce sexual violence in India. This is because the real deterrent, a criminal justice system that works, is entirely absent. The criminal justice system—policing standards, investigative protocols, or court processes and procedures—is in an abjectly broken state.”

Legal practitioners also seemed to indicate that the new laws have introduced much procedural ambiguity in an already dysfunctional system that could lead to pending cases being delayed indefinitely.

“The new laws are not well-drafted … they’re a cryptic amalgamation of several provisions. Cases [of crimes against women] filed under the new laws will get priority as there are requirements for fast-track investigations. But lakhs and lakhs of old cases pending before courts would go into dark rooms. There should be some mechanism for the closure of old cases.”

Some of the changes, which at least nominally seem stricter, might even have the counter-intuitive effect of lowering conviction rates further.

"Globally, it has been observed that it is not the severity of the punishment but the certainty of punishment that serves as a deterrent to rape. Jurimetric studies have also shown that courts are very reluctant to convict when minimum mandatory sentences are prescribed by law as it takes away the judges' discretionary power of convicting and sentencing. As it is, conviction rates are dismal and now, by introducing minimum mandatory sentences in cases of gang-rapes of minors, aggravated rape etc., it’s likely to become even worse."

The need for more humane procedures was also emphasized by lawyers DH spoke to.

"The whole criminal justice system is so geared towards punishment, it is very harsh for victims. In a rape trial, a victim is just a witness. It is the state against the accused, where is she in this whole process? Where is her dignity being maintained? ... A victim-centric approach would be being more kind and humane to her in this process."

Others, meanwhile, said that beyond legislative measures, the state should be more proactive in funding initiatives to bring about grassroots-level changes.

"What I would also like to see, structurally, is more state funding for legal awareness, for sex education, for teaching children—boys and girls—about safety and consent, for training and sensitising the police and courts to ungender their approaches. Legal reform can do little without social reform."

Focussing on the mental health and well-being of survivors is essential in such cases as well. Rape is a traumatic event that is likely to cause PTSD in at least 80 per cent of cases, as per research published in the ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry.

"We stress the importance of enhancing mental health services to support survivors effectively. This includes providing advanced training for mental health professionals to equip them with the skills necessary to handle cases sensitively and effectively. By prioritising mental health support, we can ensure that survivors receive the care they need to heal and thrive."

WHO WILL WATCH THE WATCHMEN?

Problematic lawmakers

While people usually look to their lawmakers for solutions to such situations, in India, all too often, these very elected representatives endorse rape culture.

Statements such as "Chowmein leads to hormonal imbalance, evoking an urge to indulge in acts such as rape and sex," and "One small incident of rape in Delhi advertised world over is enough to cost us billions of dollars in terms of global tourism," are among some of the absurd responses politicians have given over the years.

In fact, as many as 151 sitting MPs and MLAs in the country have declared cases related to charges of crimes against women, as per ADR data, with the BJP (54), Congress (23), and TDP (17), being the top three parties with such legislators.

As for states, West Bengal (25) has the highest number of such lawmakers, followed by Andhra Pradesh (21), Odisha (17), Delhi (13), and Maharashtra (13).

Political accountability often times is absent as well.

"Systemic change is very important but unless they implemented, we are not going to get anywhere. We believe collaboration and a buy-in by all stakeholders is integral for impact. We work with the police and civic authorities and till date we have no idea on how to access the Nirbhaya Fund. We have asked people in the system as well but nobody has any clarity."

Following the tragedy of December 2012, the Union government had set up the Nirbhaya Fund for projects specifically designed to improve the safety and security of women.

Meanwhile, Dr Nayreen Daruwalla, who is the Director of Program on Prevention of Violence against Women and Children at SNEHA, believes that it essential for those in power to “Nip it in the bud,” as she elaborates on how penalising perpetrators will ensure change.

“The onus is always on us, those at risk, to keep challenging a system that has clearly not been designed to support us. We can tell you what is broken, as we have been for decades but it is not up to us to fix it. That is for our political leaders to do, but we won't be holding our breath”.

(We'd love to hear from you! For comments and suggestions, reach out to us at webdesk@deccanherald.co.in)